Foster Wales is working to amplify young people’s voice to challenge stereotypes and stigma faced by children in care. As part of its Bring Something to the Table campaign, Foster Wales aims to correct the misunderstandings surrounding young people and the experience of fostering. The campaign was launched to mark Care Day last month – a day designed to celebrate and recognise social workers, those who have experience of care, and the importance of the sector. Molly*, from Bridgend, who is in foster care, said: “We get judged before people even get to know us. “People just think we’re troublemakers who do drugs and get pregnant underage. It’s just not true.” Alistair Cope, Head of Foster Wales, told CYP Now: “A lot of the messaging around Care Day is myth-busting, commonly around teens in care. “I’ve seen first-hand the common sort of misconceptions people have; that teens in care are bad news or come with a whole host of issues.” He explained that foster carers do not need to have particular experience, adding: “They [people considering foster care] think perhaps it takes some kind of superhero or magician to foster – someone with defined skills. “What we’re trying to do with the campaign is show that everybody has something they can bring to the table.” Cope’s top priority is to encourage people to foster through their local authorities in a bid to ensure children are not moved to out of area placements. He said that around “85 per cent of children [fostered through their local authority] stay within their locality”, this helps children to keep the same friends, school and access to family time, which maintains the stability essential for looked-after children. Cope added that this statistic drops to around 20 per cent when a child is placed through private residential or foster care agencies. According to StatsWales, the number of children in care has reached more than 7200. “We’re at unprecedented numbers of children in the care system. We’ve got a really ambitious aim to recruit 800 carers by 2026 across Wales, and this campaign is just the start of that process”, said Cope. *Names of some young people have been changed to protect their identities. Source: www.cypnow.co.uk/  Ofsted has today published results of a survey asking children, learners, parents, foster carers, social workers and other professionals about their experiences of children’s social care. Most children in foster care always feel safe, according to an Ofsted survey. There were 45,655 responses, including 6,614 from children, to the survey. Almost all of the children in foster care (99%) who responded said they always feel safe where they live and are more likely to always feel safe compared to children in other types of care. Responses were similarly positive among children living in children’s homes, with 95% saying they felt safe where they lived ‘always’ or ‘most of the time’. Read the ‘Children’s social care questionnaires 2023’. One child in foster care wrote: "My carers are great, this is my first stay away from home and I was very scared, but they made me feel welcome and part of their family. I still get to see my own family, as well, and my carers have explained everything to me as we go along. I really struggled going to sleep at first, but my carers were really good with me, sitting at the end of my bed for hours till I fell asleep." When asked for their general views, children often spoke about their overall enthusiasm for the place they lived or stayed, describing it as being brilliant or similar. Many children staying in group care or living in foster care said that they would like to stay where they are until they were 18 or forever. Most children in group care reported that they got along with other children and adults where they lived or stayed, although more said they got on with adults compared with those who said that they got on with other children. One child living in a children’s home wrote: "I really like where I live because the staff, the manager and the area manager, all of them support me a lot of the time. The staff make me dinner and I really like it because they all are good cooks. The children are really supporting as well including the adults." However, 12% of children in boarding schools and 9% of children staying in further education (FE) colleges said that they got on with the adults where they live ‘sometimes’ or ‘never’. Ofsted’s Chief Inspector, Amanda Spielman said: "I would like to thank everyone who responded to our annual survey. These surveys give us an opportunity to hear first-hand from people working across children’s social care and from children and young people about their experiences." "All children deserve to feel happy and safe where they live, so I was particularly pleased to see so many positive experiences." Source: www.gov.uk/government/news/  John Lewis Partnership offers new and existing foster carers within its company additional paid leave. The retailer has received a Foster Friendly accreditation via the Fostering Network for its ongoing support to care experienced people John Lewis Partnership is to offer additional paid leave to all new and existing foster carers within its business. From today, John Lewis and Waitrose partners will receive an additional week of leave as the high street stalwart looks to strengthen its commitment to support care experienced people. The Partnership has also become the largest organisation to receive Foster Friendly employer accreditation from the Fostering Network. The accolade comes seven months after the retailer launched its Building Happier Futures programme to support the care experience community. John Lewis chair Sharon White said: “We are incredibly proud to be giving even more support to our Partners who are foster carers. “They will now qualify for an additional week of paid leave, meaning they will have more flexibility to balance all the things they need to be great foster carers – attending appointments or undertaking training. “We are delighted to be playing our part to support foster carers as part of a broader programme of helping care experienced young people to get access to jobs and training in the Partnership.” Last week, the retailer revealed it had teamed up with online safety organisation Internet Matters to train staff to become experts in family technology and offer specialist advice on internet safety. Source: www.retailgazette.co.uk/blog/  Fostering Associations from across the UK have formed a national consortium to better coordinate support and guidance for carers. The National Fostering Association Consortium also aims to ensure the skills and qualifications of foster carers are better recognised in the care sector. It also aims to lobby the Department for Education on foster care issues. Supporting the consortium is Foster Support, a not-for-profit company that focuses on improving retention and recruitment among foster carers. A focus is on promoting collaboration and sharing of good practice among fostering groups across the UK as well as with councils’ children services departments. According to Foster Support director Jane Collins the consortium’s focus on collaboration has been modelled on an arrangement Surrey Fostering Association has with its local authority to ensure “foster carers’ views and voices are head and respected”. “Over the past few months, we have held a number of joint meetings with fostering associations around the UK which culminated in the decision to form a national consortium to bring everyone together under one banner,” she said. “The aim will be to share good practice. We have also set out national minimum standards for fostering associations which include expectations around how fostering services work with their associations.” She added that too often local fostering associations “are ignored” and only have a “token tick box role” locally “such as organising a Christmas party”. Surrey Fostering Association chair Jane Porter said the consortium “creates an opportunity for different fostering associations, to share their knowledge and experiences, in both foster carer support and proactive discussions with a fostering service; some of which may have been good, or sadly not so good”. Earlier this month it emerged that more than half of foster carers have considered giving up the role due to the cost-of-living crisis. Nine in ten say they are having to cut back on spending on children and two and a half per cent have used food banks. Source: www.cypnow.co.uk  Foster carers are in short supply in Britain and confusion over pay may be partly to blame. Here’s what you need to know There is a hug at the end of the novel Matilda that never ends. It is the one Miss Honey gives Matilda when her parents abandon her. “Matilda leapt into Miss Honey’s arms and hugged her, and Miss Honey hugged her back,” Roald Dahl wrote in 1988. Today, foster carers like Miss Honey are in short supply. Since 2014, the number of children coming into care has risen by 11%. Yet it is estimated that 12% of foster carers left the sector last year, triggering what has been described as a recruitment and retention crisis. “There is a massive shortage of foster carers,” says Vicki Swain, a spokesperson for the Fostering Network charity, which represents foster carers and services. She says more than 9,000 new foster carers are required across the UK to make up this shortfall. “We need skilled people who have the patience and ability to completely turn a child’s life around,” she says. A lack of awareness of how it all works financially – how much you can earn and the costs involved – may be preventing some people from coming forward. In fact, some can earn a lot. Essex county council says: “Some foster carers earn up to £1,000 a week, which is £52,000 a year.” However, many foster carers do not like to talk about money, the Fostering Network told Guardian Money – and it is fair to say that we struggled to find one who was prepared to speak publicly about their finances. One anonymous foster carer told Money that if fostering services and local authorities were more upfront about the fees they pay, more people would realise that fostering was something they could afford to do. So how do you become a foster carer – what does it involve and how much do you get paid? What costs are involved, what are the tax implications, and can you get help with any of the expenses? Becoming a foster carer Foster carers do not need to be married, heterosexual or in a relationship, and they do not have to be a homeowner or have children of their own. You can even have a criminal record, as long as the offences are minor and do not relate to a crime against children or a sexual offence. You do, however, need to be over 18, live in a home where you can provide a bedroom for each child you foster, and – most significantly – you must be prepared to give up your job and devote yourself to your foster children, if necessary. “The needs of some children will be so significant that fostering services look for people who don’t work or are able to give up work once they are approved as a foster carer,” Swain says. You will be quizzed about your views Before you get approved, you will be asked to participate in a thorough assessment process with a fostering service that typically lasts four to six months. You will be asked for your views on a range of topics, including parenting, equality, religion, sex and disciplining children, to ensure you are suitable to look after a vulnerable child, and the fostering service may ask to see your bank statements, credit card bills and mortgage or tenancy agreements. “They will look at whether you’re financially stable,” Swain says. Anyone who is in debt and struggling to make ends meet or in any danger of losing their home would be deemed unsuitable.” You will then be asked to complete a free training course as part of the assessment process. The training focuses on the practical skills you will need as a foster carer and examines why vulnerable or traumatised children may exhibit challenging behaviour, and how best to assess and sensitively respond to their needs. What you will be paid In the UK, all foster carers are given an allowance to spend on the child. The amount varies according to where you live, the child’s age and whether they have specific needs. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, the minimum is usually between £137 and £240 a week, although some local authorities pay less. In Scotland there is no national minimum allowance, although the Scottish National party pledged in 2007 to introduce one. “Fifteen years on, they still haven’t done it,” Swain says. “That’s a whole generation of children in foster care who have missed out.” Some fostering services in Scotland pay as little as £70 a week, Swain says. Others pay £200. The Fostering Network says 63% of foster carers also receive a fee, on top of the allowance. While the allowance is spent on the child, the fee payment recognises your time and skills, “because obviously lots of foster carers are told to give up work in order to foster”, Swain says. The fees can vary: for example, the Essex county council website states that, on average, its foster carers earn £483 a week (£25,116 a year), and earn more for fostering older children and those with complex needs or disabilities. It adds that on top of a fee, you get a weekly allowance of up to £236.95. In a recent survey by the charity, only 9% of foster carers said they received a fee that was at least equivalent to working 40 hours a week at the “national living wage”. Meanwhile, a third said their allowances did not meet the full cost of looking after a child. “Many foster carers do spend out of their own pockets to top up things,” Swain says. Despite this, many say the role is highly rewarding. Fostering, the charity says, has the power not only to transform children’s lives but also the lives of foster carers. Choosing a fostering service Although it is often in the best interests of a foster child to remain in their local community, you can foster with any nearby local authority – it does not have to be the one you live in. Alternatively, you can sign up with an independent fostering service, although it is worth bearing in mind that some of these independent organisations make large profits. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, you can sign up with only one service – you cannot be approved to foster with multiple services at the same time. Since the support that different services offer varies, it is a good idea to shop around and interview the fostering service as much as they are interviewing you before you commit to one, Swain says. For example, ask what the likelihood is that you will always have a placement. This is important because you will receive fees and allowances only when a child is in your care – although in some circumstances, some fostering services will pay a retainer fee when you do not have a child in placement. It is vital to think ahead and consider how you will support yourself financially when a child is not placed with you. The nature of foster care means people who do it are altruistic and do not like to talk about money because it is for looking after children, Swain says. “But getting the right level of financial support is important. You need to be able to meet the needs of the child you’re looking after and, if you’re giving up work in order to foster, you need to pay the bills, too. Nobody fosters for the money but it is really important you get enough support.” Help with other costs Some local authorities offer financial or other rewards to their foster carers to encourage more people to take up fostering, such as several weeks of paid holiday each year or expenses for travel related to your role. “There are an increasing number of local authorities that will exempt you from council tax if you’re a foster carer,” Swain says. You may also be able to get an initial placement grant to help with the initial costs of a child’s wardrobe or be provided with free equipment such as a cot. “Some children come into a foster placement without a possession, without anything in the world,” Swain says. In addition, you may receive small one-off payments on your foster child’s birthday and at Christmas or other religious holidays,to help cover extra costs. Often, foster carers receive free or discounted entry to leisure centres and family-friendly events or theme parks. Tax relief on your fostering income As a household, you will not have to pay tax on the first £10,000 you receive from fostering. This is in addition to your individual tax-free personal allowance (usually £12,570). You will also get additional tax relief for every week you foster a child: £200 a week for every child under 11, and £250 a week for older children. So, for example, if you foster a six-year-old for a whole tax year and a 15-year-old for 10 weeks, you will receive £10,000 of fostering tax relief that year, plus a further £10,400 of additional tax relief for the six-year-old and another £2,500 of tax relief for the 15-year-old, as well as your personal allowance of £12,570. So, theoretically, you could receive £22,900 from fostering that year and then potentially earn another £12,570 of income on top of that – and not pay any income tax on £35,470 in total. If you did so, it would be equivalent to earning a gross salary of about £47,000. However, since the amount of tax relief foster carers get is often greater than the allowances foster services pay, it would be wrong to assume you would receive this much money in practice. When you start fostering, you will need to register as self-employed and file tax returns. This will allow you to claim tax relief. Entitlement to benefits Fostered children are not counted as part of your household when any means-tested benefits are calculated, and you will not usually receive child benefit or child tax credit for a foster child. Equally, the allowances and fees you get from fostering are normally disregarded as income when calculating your eligibility for means-tested benefits. For tax credits purposes, only your taxable profit arising from fostering will be taken into account. As long as you satisfy the other eligibility rules, you can claim universal credit, for example, and the money you receive from fostering should be ignored when working out how much you can get. If you are receiving help with housing costs through universal credit, you can include an extra bedroom if you are a foster carer. One anonymous foster carer talks about money “Pay is something many people in fostering don’t like talking about. There is a perception that if you are upfront about the allowances that are paid, you may attract people into fostering for the wrong reasons. But I don’t agree with that. I think there are plenty of people who would make terrific foster carers but who aren’t considering it because they don’t think they could afford to do it. “I would certainly make an educated guess that, for many people, the fees paid would cover one person in their household giving up work to become a full-time foster carer. And this is separate to the money they receive to cover the costs of a child living in their home, such as their food, clothes and energy. “I don’t think anyone fosters for the money. The money is important because it enables people to foster but it isn’t the reason someone would open their house and their family to looked-after children. But I do think ignorance about the financial arrangements in foster care is a barrier to more people coming forward. “I think if agencies and authorities were more upfront about the fees they pay, more people would realise that fostering was something they could afford to do.” This article was amended on 16 August 2022 to clarify that a foster carer must be prepared to give up their job “if necessary”; the government’s advice is that a carer “may be able to work and foster. Whether you can depends on the child’s circumstances and the fostering service you apply to.” Source: www.theguardian.com  A survey of foster carers conducted by FosterWiki has highlighted the serious financial pressures on the sector as the cost of living crisis continues to mount. This echoes the findings of our State of the Nation 2021 survey of over 3,000 foster carers, which showed that for over a third of foster carers their allowances do not meet the full cost of looking after a child. As we conduct our annual review of allowances, we have found that around two thirds of services in England have increased their allowances so far, and we expect others to follow suit. However, in light of these recent survey results, it is clear that more needs to be done to ensure that foster carers are provided with adequate financial support to meet all the needs of the children they care for. In our State of the Nation 2021 report, we urged governments across the UK to undertake a comprehensive review of the minimum levels of fostering allowances set in their respective countries – these are now well overdue. In Scotland, there is still no national minimum allowance for foster carers in place, so the Government must take action now to introduce and fund this. If foster carers are to continue providing stable, loving homes for children and young people, they must be well funded to do so. It is the responsibility of all UK governments to ensure this happens. Source: www.thefosteringnetwork.org.uk Fostering News: UK is failing fostered children with mental health problems, warns charity26/6/2022

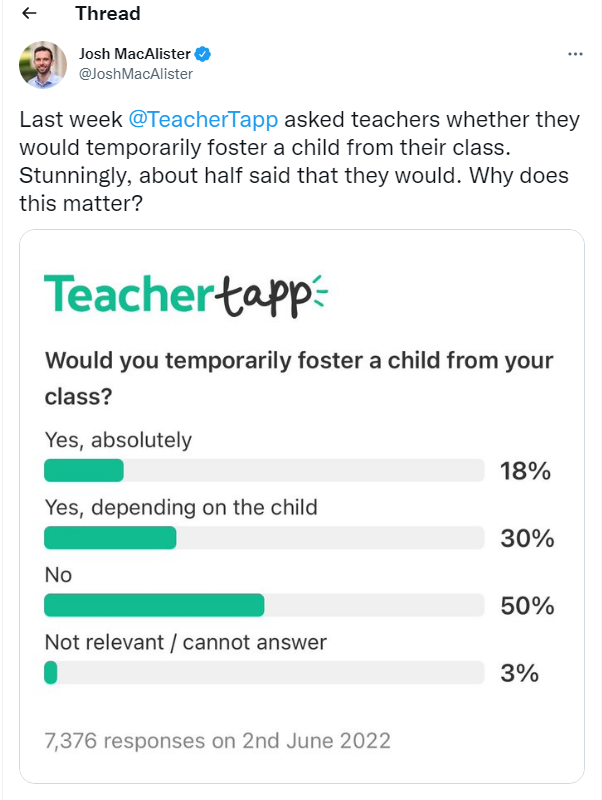

Report suggests half of all foster carers are looking after a child with complex needs Foster care in Britain is facing a “mental health crisis” because the government is failing to meet the needs of mentally ill children in care. That is the damning verdict of the latest report from the Fostering Network, a charity representing foster carers. The report, shared with the Observer, suggests half of all foster carers are looking after a child with complex mental health issues, such as anxiety, depression and attachment and eating disorders. Yet only a quarter of the 3,352 foster carers surveyed by the charity said their foster child was receiving help with their mental health problems. Another quarter reported they were looking after a foster child who needed mental health support but was not getting it. The charity’s head of policy and campaigns, Jacqui Shurlock, said the findings reveal a “significant area of unmet need for children in foster care” and suggest a “mental health crisis” may be looming in the sector. “We know, from the fact that they’re in care, they will have experienced trauma,” said Shurlock. “But we weren’t expecting to find that percentage not getting any mental health support at all. “A good home life makes a massive difference to children,” she added. “But foster carers can’t do everything. Where children have mental health needs, foster carers need support from mental health services – they can’t deal with that burden all on their own.” She called on the government to stop expecting foster children to restart their referral to child and adolescent mental health services (Camhs) when they move to a new foster care placement in a different local authority or NHS trust. Another barrier placed in front of foster children is that their short-term foster care placements can be deemed not “stable” enough to enable them to qualify for support – for example, because the child is waiting to hear from a judge about whether or not they will go back to their birth family. “Imagine how difficult that situation is for a child. That might be the very time they most need mental health support,” said Shurlock. By failing to meet that need in a timely fashion, “we are obviously risking much more negative outcomes in their lives, which could be avoided”. The report also showed foster carers face a similar battle when caring for a child with foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), which occurs when prenatal alcohol exposure affects the developing brain and body of a foetus, causing permanent health, developmental and behavioural problems. Nine per cent of foster carers said they had looked after a child diagnosed with FASD. A further 13% said they had cared for a child with suspected FASD in the last two years, suggesting significant numbers of foster children with the condition are falling through the cracks in the system. Children in care, Shurlock said, are simply not being valued and supported the way they need to be. “It feels like the state is failing in its duty to meet the needs of those children.” She suspects the “near impossible burden” this places on foster carers may be one of the reasons why around one in five fostering families left fostering last year. About 9,200 new foster families are now needed across the UK. In Essex, Darren Harman-Page and his partner Karen have been fostering children for over 27 years, caring for more than 100 foster children and adopting six. He said some of the traumatised and neglected children they have fostered who have severe mental health needs are still waiting for support, more than two years after they were referred to Camhs. “It’s really tough,” he said. Children in these circumstances may struggle with anxiety and self-harm or become hypervigilant or aggressive. They may also feel overwhelmed or unsafe in what others may perceive to be “normal” everyday situations. “Their ‘normal’ was chaos and neglect.” He is doing all he can to provide the children he fosters with a secure and loving home, but finds it heartbreaking – and frustrating – when these children, who have suffered so much already, are not able to access the mental health support they so obviously need. “You feel terrible. That’s where the sadness creeps in, I suppose. Because you haven’t been able to help them.” Source: www.theguardian.com  Care Review chair Josh MacAlister has set out an argument for one per cent of all teachers to foster a child at their school. In his recommendations to the government, MacAlister called for the recruitment of 9,000 new foster carers in England over three years. “Family group decision making processes should identify adults known to the child (e.g. teachers, community workers or the parents of a child’s friend) who might be willing to foster,” the review's final report states. Following its publication, MacAlister shared a poll by Teacher Tapp on Twitter which shows that almost half of teachers asked said they would temporarily foster a child from their class. However, of those who said they would, 30 per cent said their decision would “depend on the child”.

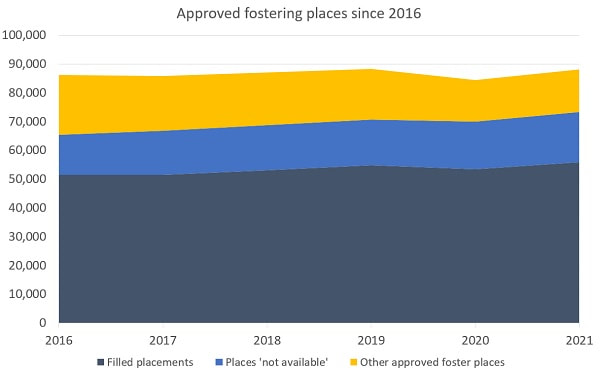

Some 50 per cent of those polled said they would not foster a child from their class. MacAlister said in a series of tweets accompanying the poll results: “Young people with care experience told me time and again that they wished their teachers would have been asked to care for them. “Having a teacher or another adult who already knows a child becoming a foster carer might not be possible or right for every child (or the teacher). But going into care can be enormously isolating, can disrupt school life and can fracture relationships. “If only one per cent of teachers stepped forward to foster a specific child, there would be 4,610 new homes available for children. Surely this is worth a try,” he said. Teachers, care leavers and sector leaders have shared mixed opinions on the idea on Twitter. Some called for more clarity around the idea of “temporary” arrangements. Richard Barker, emeritus professor of child welfare at Northumbria University, described the poll as “worthless”, writing: “Not least because it doesn’t define temporary – a weekend, a fortnight, a year?” Lisa Cherry, schools, services and systems consultant, added that MacAlister's call was a “disappointing discourse, for many reasons”. “Teachers are working 60-hour weeks and children and young people who are 'looked after' need connection on speed. “Fostering and teaching perform entirely different functions that cross over as the most important domains in a child's life. This is a lame recruitment strategy,” she said. One person, who has experience of foster care, added: “Teachers were often the only stable and consistent relationships I had. “I wouldn’t have wanted to jeopardise that by it becoming a formal arrangement, and at the risk of the placement breaking down and then being moved on from the one person that I trusted.” However, one adoptive parent, who works in an alternative provision, said: “I love this. If my boys or their siblings had been able to have been looked after by someone who knew them when they were taken into care, even if it was just for a little while then the huge trauma of being separated from everything they know would have been a little bit easier.” Source: www.cypnow.co.uk  Foster Care Fortnight™ is The Fostering Network's annual campaign to raise the profile of fostering and show how foster care transforms lives. Foster Care Fortnight 2022 takes place from 9-22 May. Foster Care Fortnight™ is the UK’s biggest foster care awareness raising campaign, delivered by leading fostering charity, The Fostering Network. Established in 1997, the campaign showcases the commitment, passion and dedication of foster carers. It also supports fostering services to highlight the need for more foster carers. Thousands of new foster families are needed every year to care for children, with the greatest need being for foster carers for older children, sibling groups, disabled children and unaccompanied asylum seeking children. Running from Monday 9 May until Sunday 22 May, our theme this year is ‘fostering communities’ and we will use the campaign to shine a light on the many ways people across the fostering community support each other. Throughout the fortnight, The Fostering Network will be running events, sharing content on our social media channels and making as much noise as possible about the transformative power of foster care, and we want you to get involved too. Whether you’re a foster carer, a social worker, young person or supporter of foster care you are part of a community making a real difference to the lives of young people, and we want to celebrate the impact you all have. How to get involved Join the conversation Use #FCF22 and #FosteringCommunities on social media to join in with the campaign, sharing your stories and experiences of how the fostering community has supported you, or what fostering means to you and your community. Resources are available here to help you get the word out. Fundraise and donate The Fostering Network works hard to influence change, promote fostering and provide support, and every donation we receive helps us to continue this work. Join in with Foster Walk, or make a donation to support our work. Join an event The Fostering Network is hosting a number of events for our members throughout the fortnight, which you can find out about and register for via our website – we hope to see as many of you as possible! If you have any queries about Foster Care Fortnight please contact [email protected] Source: www.thefosteringnetwork.org.uk  Regulator says rise in placements is not enough to meet growing and increasingly complex demand England’s care system needs an “urgent boost to the number of foster carers” to avoid reaching “breaking point”. That was the warning from Ofsted as it released its annual fostering statistics last week, which showed there were 88,180 approved fostering places, 55,990 of which were filled, and 45,370 approved fostering households, as of 31 March 2021. But despite the latter being a record figure, Ofsted said the statistics painted a “bleak picture”, with “too few carers with the right skills” to support the number of children needing a placement. Over the past five years, the number of approved places and approved households have only increased by 2% while the number of children in placements rose by 9%. Increases driven by family and friends carers And this increase has been driven by a rise in family and friends carers, who are usually approved to care for specific children and the vast majority of whom do not offer other placements. Over the past five years, the number of approved households whose primary placement offer was for family and friends care rose from 5,855 to 8,045. Discounting these, the number of approved fostering households decreased by 3% to 37,325, with no change in the number of placements primarily for permanent care and a fall in those for non-permanent care. And of 8,880 households newly approved in 2020-21 and still active at the end of the financial year, 3,525 (40%) were family and friends carers. These figures correlate with the government’s children looked after statistics for March 2020, which showed that the proportion of children in foster care not with a relative or friend had decreased to 57% from 60% in 2018. Lucy Peake, chief executive of charity Kinship, said the figures showed that it was becoming “increasingly urgent” that the government recognises and values kinship care. ‘Bleak picture’

Ofsted’s figures also showed the effective capacity of the system had fallen over the past five years, with the number of vacant places plummeting from 21,160 to 14,005. This was mainly due to the rise in filled places over this time, but it was also caused by the 3,525 rise in “not available” places, which reached 17,390 in 2021. Yvette Stanley, Ofsted’s national director for social care, said the figures painted a “bleak picture”. “[Year] on year we see more children coming into foster care, and too few carers with the right skills to give them the support they deserve. How long can this go on before the care system reaches breaking point? “We rarely see children coming into care who don’t need to be, but with the right help earlier, some may be able to remain with their families. We also need to urgently boost the number of foster carers, making sure they, and the children they care for, get the right support.” Fewer enquiries leading to applications Ofsted also highlighted the fact that the proportion of enquiries from prospective fostering households that led to applications has decreased in recent years. While the number of enquiries from prospective fostering households increased by 57% to 160,635from 2015-16 to 2020-21, .the number of applications only rose by 18% to 10,145. This means the proportion of applications from enquiries decreased from 8% in 2015-16 to 6% in 2020-21. A lower proportion of initial enquiries to independent fostering agencies (IFAs) converted to applications (4%) compared to local authorities (15%). The proportion of fostering applications processed in the year that were approved also decreased, from 44% in 2015-16 to 32% in 2020-21. Sixty five per cent of foster carers approved in the year to March 2021 were over 50 while 26% were over 65, both similar rates to the year before. Directors call for ban on profit-making agencies The Association of Director of Children’s Services (ADCS) said the figures showed government needed to invest in recruiting more foster carers. “A wider pool of foster carers, who can meet the diverse needs of children and young people coming into care, will lead to greater placement choice, and as a result greater placement stability,” said Edwina Grant, chair of ADCS’ health, care and additional needs policy committee. “However, without the support from national government this is becoming increasingly difficult as the number of children coming into care continues to rise.” Grant also called for an end to “significant profits being made by a small number of organisations from fostering” and urged the care review to address this. “Such practices cannot be justified, and we reiterate our call on government to introduce legislation, similar to that in Scotland, which prevents for-profit operations in this area,” she said. Call on government to fund recruitment drive Andy Elvin, chief executive of fostering charity TACT, also agreed that more foster carers were needed and called on central government to intervene by funding a national carer recruitment campaign. Elvin alluded to his idea – proposed for consideration by the care review – of a “national care family”, where responsibility for recruitment of foster carers would be taken out of councils’ hands. “152 local authorities working separately are never going to join up effectively to do this. We need to move towards larger regional and/or national structures to operate the care system and take responsibility for adopter and foster carer recruitment,” he said. The network said the increases in carers reported by Ofsted fell short of what was needed to meet demand. ‘Children should be listened to’ It previously estimated that 7,300 more foster families were needed in England when considering the specific need for households willing to care for teenagers, sibling groups, disabled children, and unaccompanied asylum-seeking children. Katharine Sacks-Jones, Become’s chief executive, said the recruitment of carers had to be specific to children’s needs. “Children need foster carers who can welcome sibling groups to prevent young people’s trauma being deepened through further separation,” she said. “They need foster carers in their local area to enable them to retain the relationships and links to the communities which matter to them. “Children and young people in care should always feel their thoughts are listened to and acted on where possible during the process of matching them with suitable foster carers”. More recruitment ‘could be costly’ However, Harvey Gallagher, chief executive of the Nationwide Association of Fostering Providers (NAFP), said simply recruiting more foster carers could be costly and inefficient “If it were possible to recruit many more foster carers to offer more choice for children, we would have to be willing as a society to fund vacancies,” he said. “Foster care, as well as being a vocation, is also income for foster carers to be able to pay their bills, and they only receive fees when a child is living with them.” Gallagher called for better support for children in placements and also said tackling poverty and poor mental health in families could ease demand on the care system. ‘Not everyone can be a foster carer’ He defended IFAs’ lower rate of applications resulting from enquiries about being a foster carer. “Not everyone is suited to being a foster carer, so IFAs undertake a stringent process when speaking with anyone enquiring about being a foster carer,” he said. A spokesperson for the DfE said: “Local authorities are responsible for all children in care in their area, including those in foster care. “We have made significant additional funding available in response to changing pressures on children’s services and we are investing in different approaches to help councils provide foster care places, including through digital tools that make it easier to match children with foster carers, and by trialling different ways to plan placements.”

Source: https://www.communitycare.co.uk |

News & JobsNews stories and job vacancies from our member agencies, the fostering sector and the world of child protection and safeguarding as a whole. Browse Categories

All

|

|

The Fairer Fostering Partnership

c/o TACT Fostering Innovation House PO Box 137 Blyth NE24 9FJ |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed